STANDING TOGETHER: Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Women’s Suffrage

A Photo Essay by Jeanine Michna-Bales, 2016 - 2020: Project Research and Principal Photography from 2012 - 2020

VISIT THE PROJECT WEBSITE AT StandingTogether-project.com. It includes some historical research and a behind the scenes look that went into the making of the series, in addition to educational resources like lesson plans and online links.

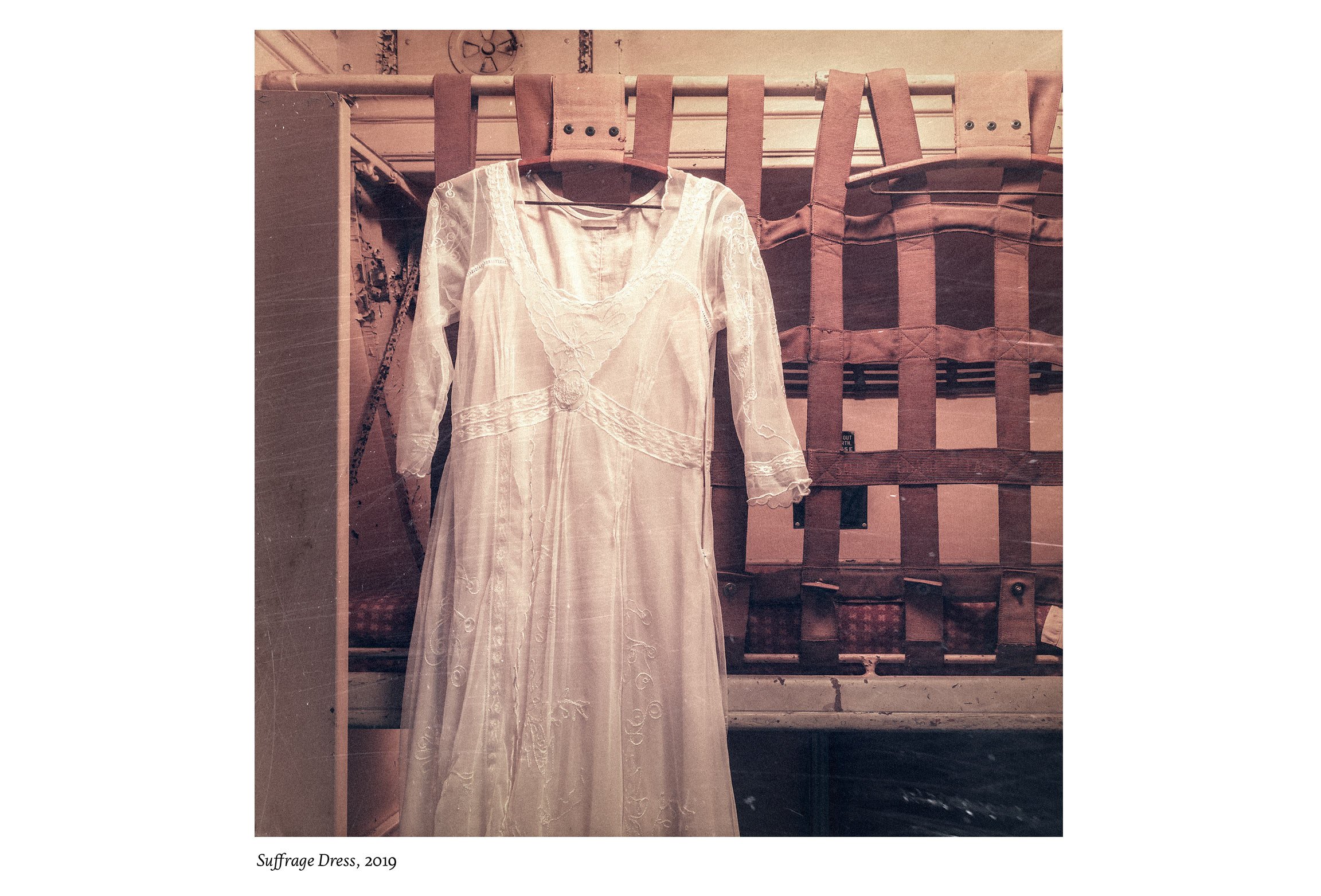

Since 2016, Michna-Bales has been researching the Suffrage chapter of American history. Standing Together champions a little-known figure who was at the forefront of the suffrage movement in the early 20th century, Inez Milholland Boissevain (1886 – 1916).

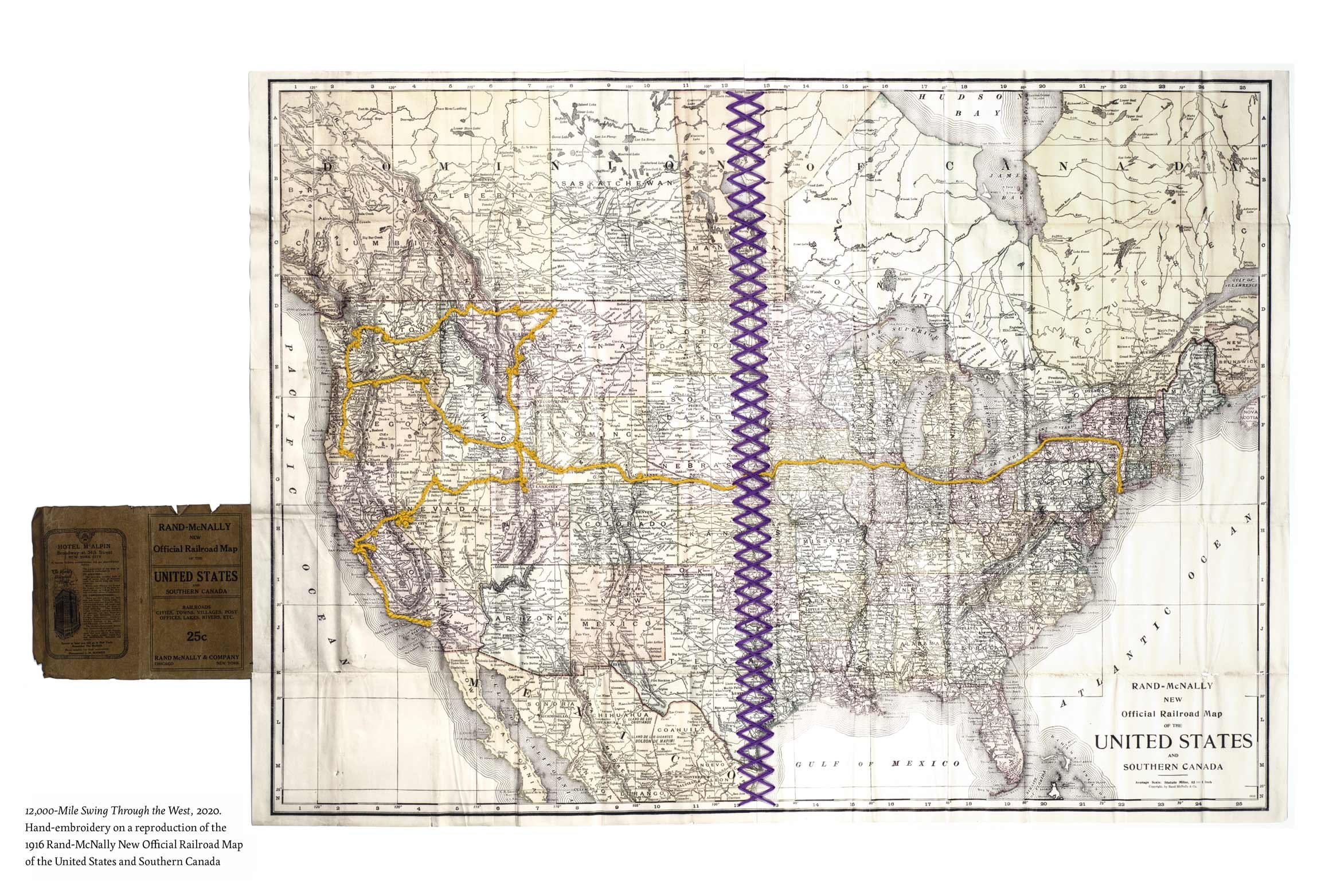

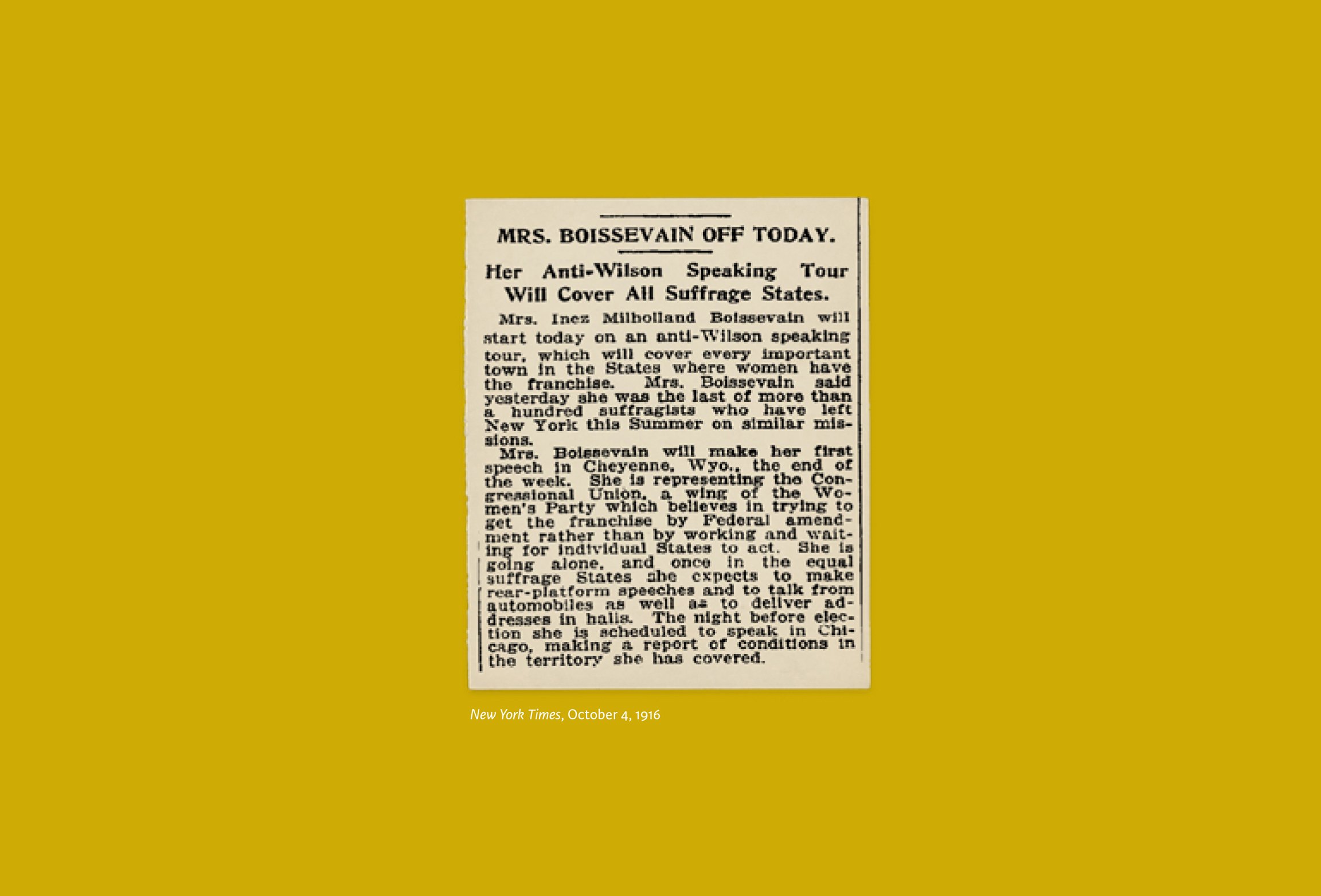

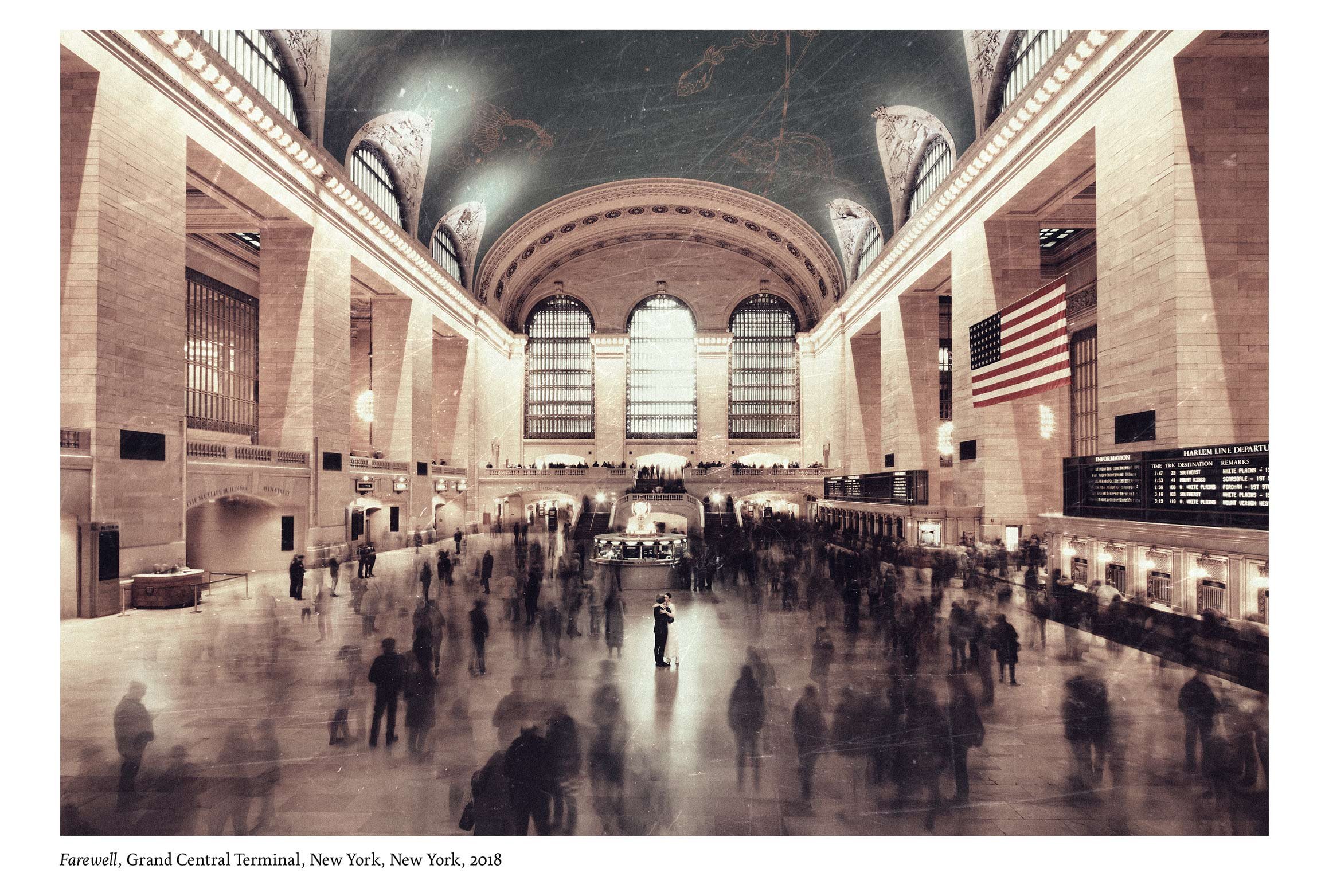

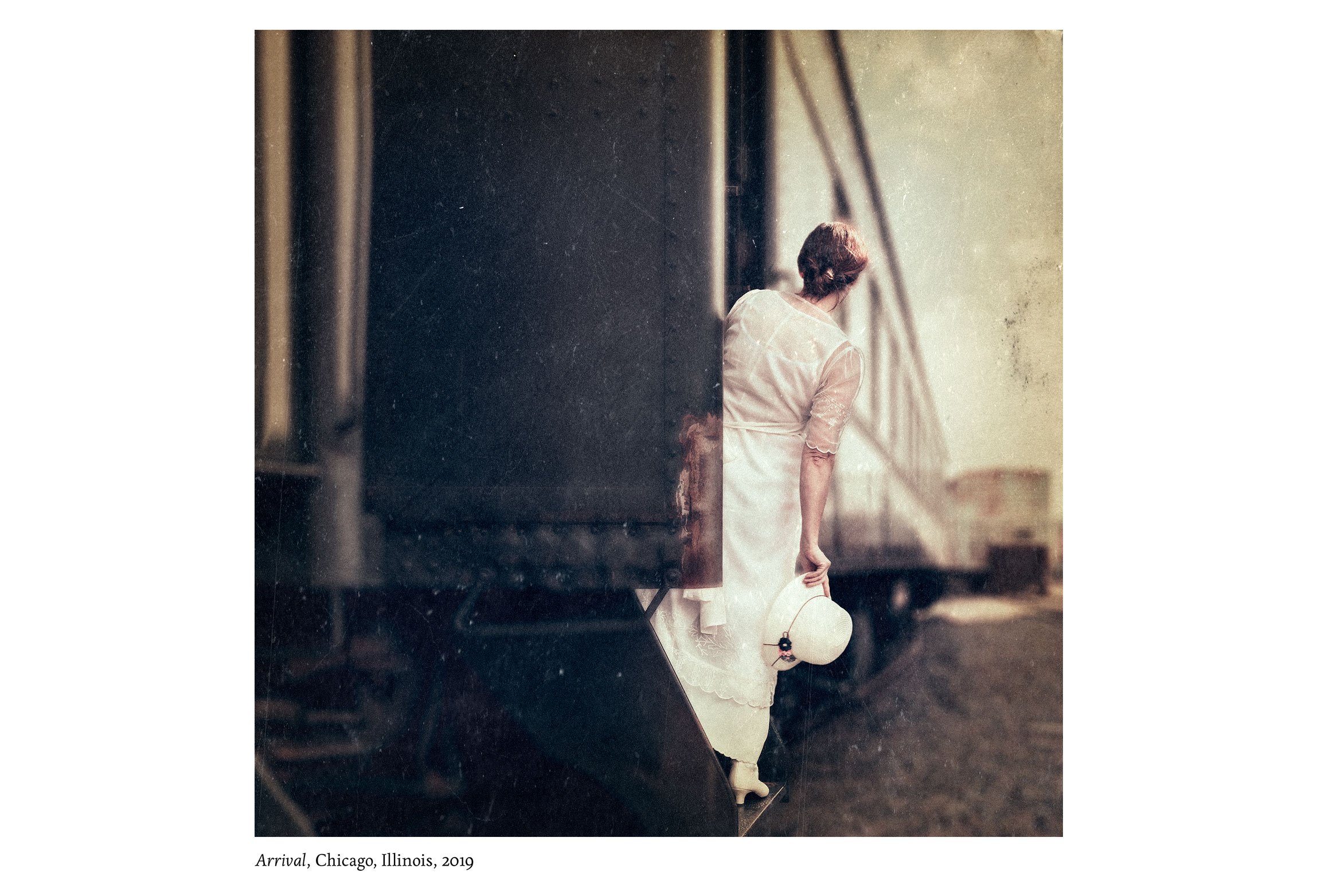

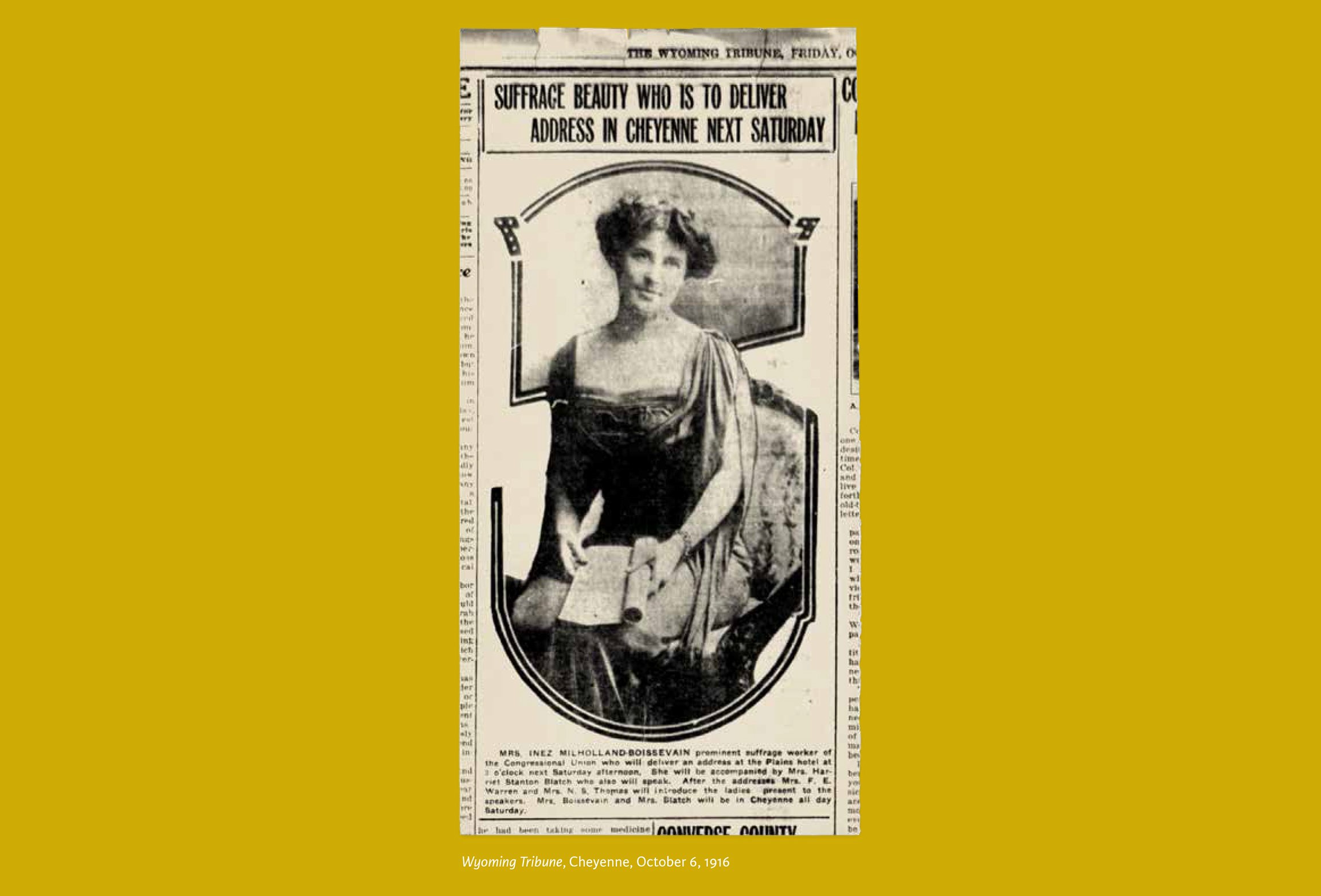

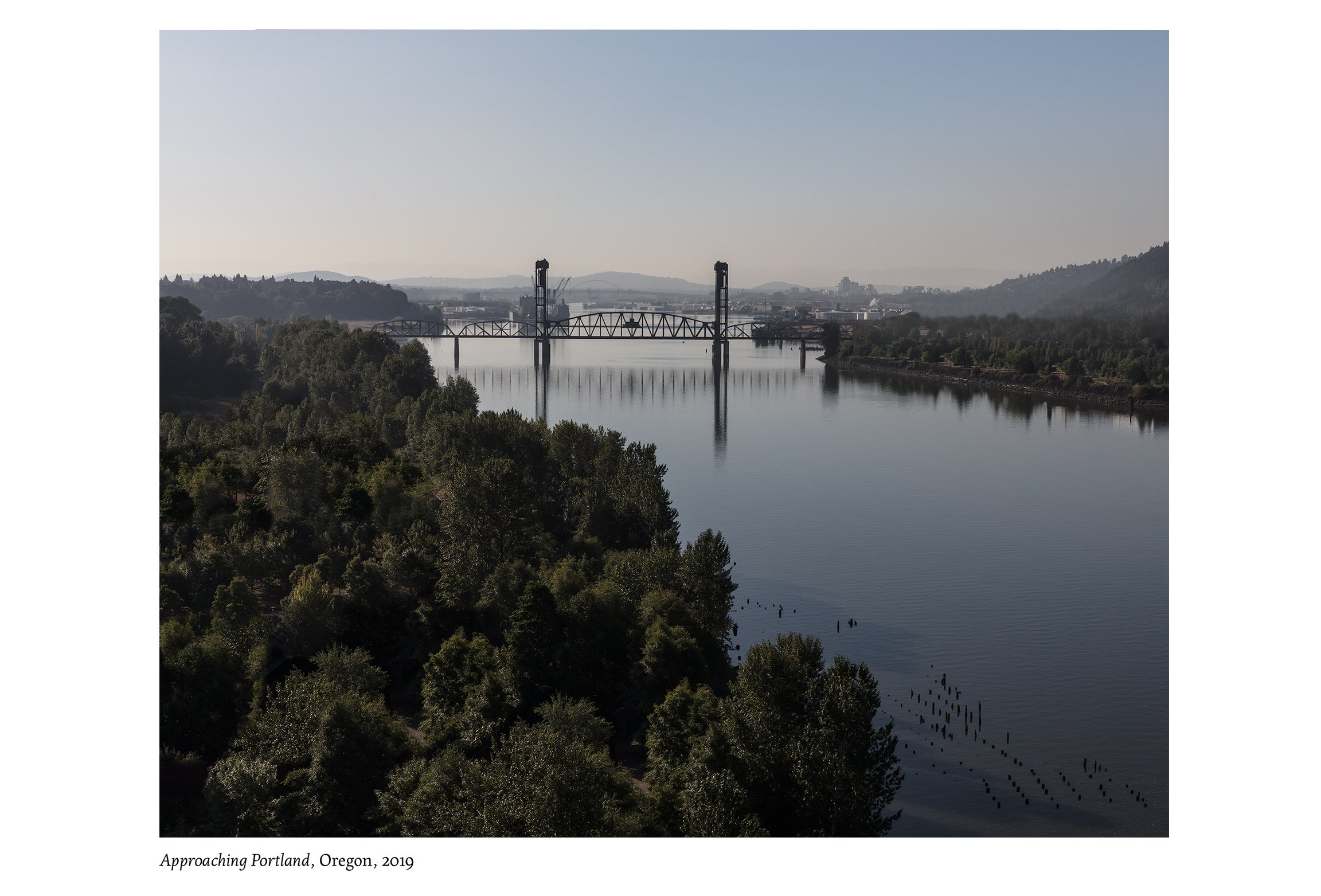

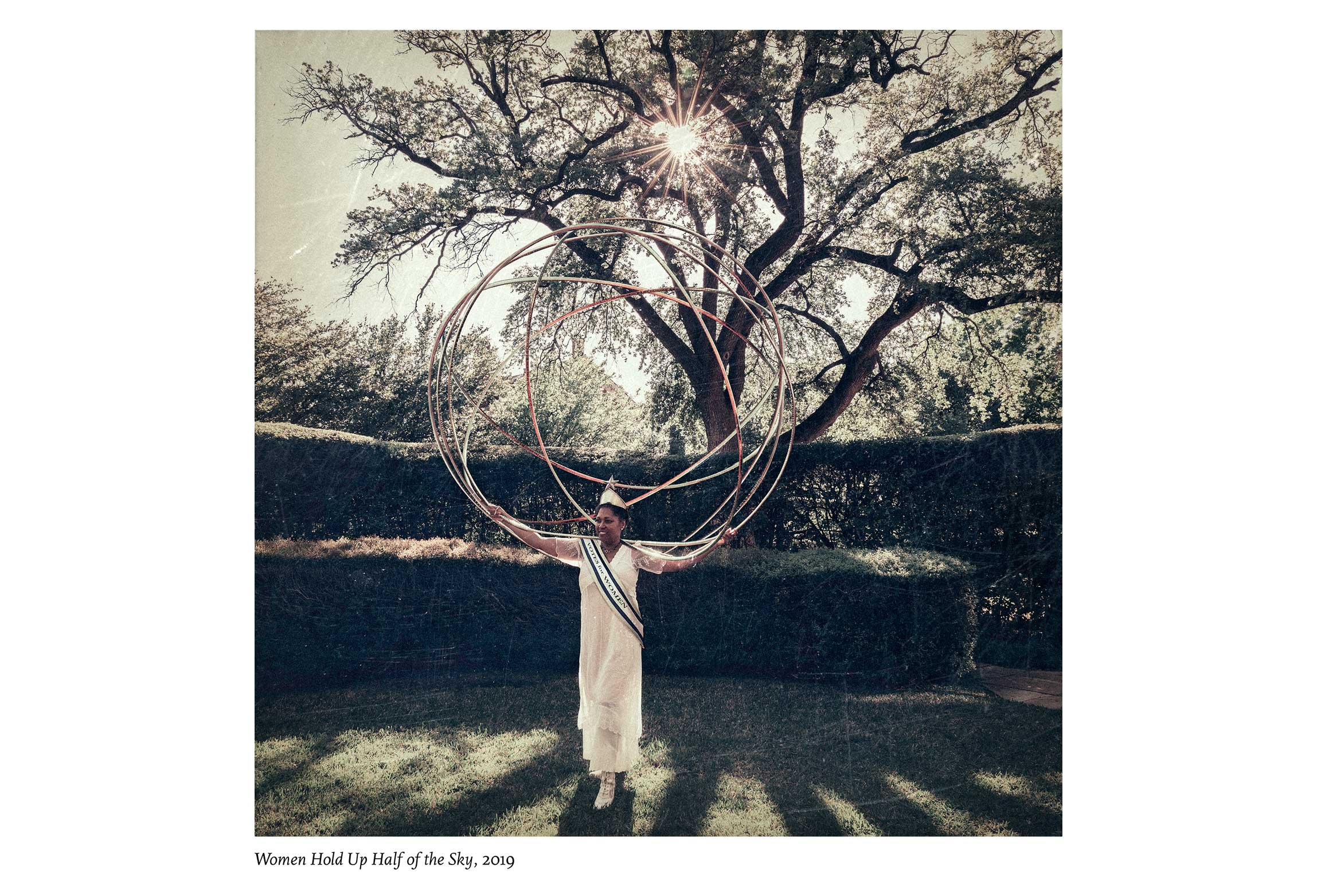

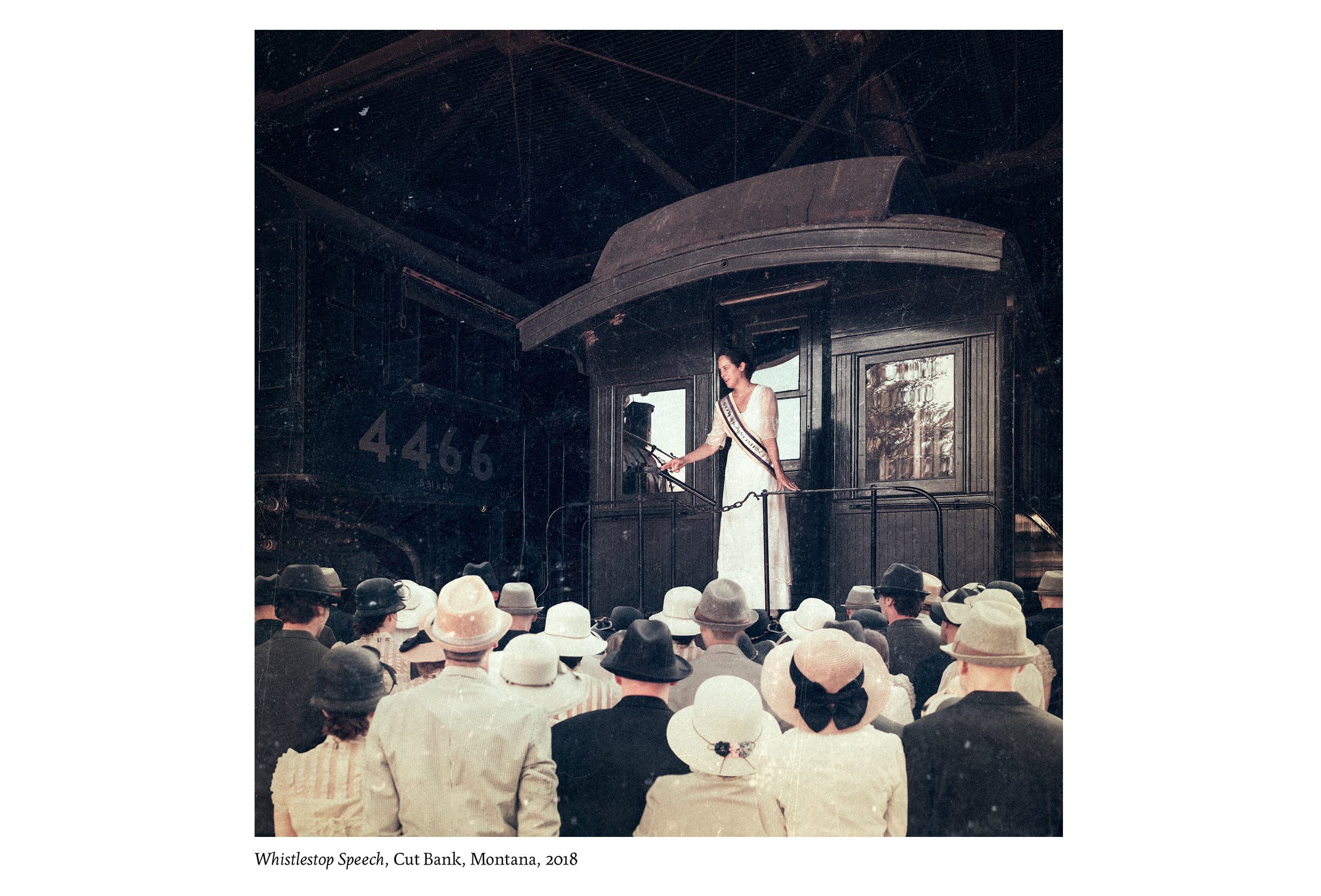

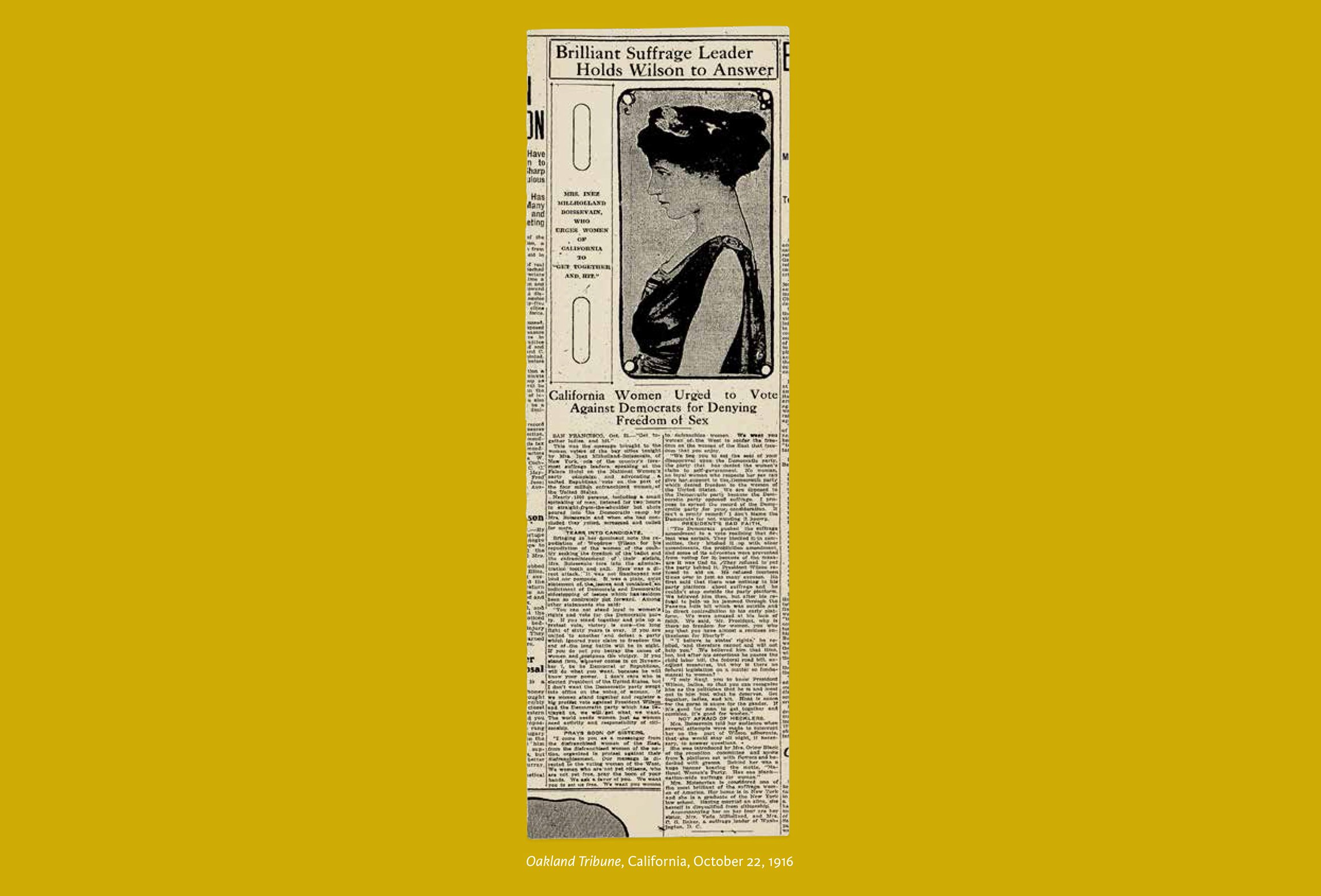

In October 1916, suffragist Inez Milholland was appointed as a “special flying envoy” to make a 12,000-mile swing through the American West. She was part of a radical campaign by the National Woman’s Party to send dozens of suffragists from the East out to 12 Western states and territories where women had the right to vote.

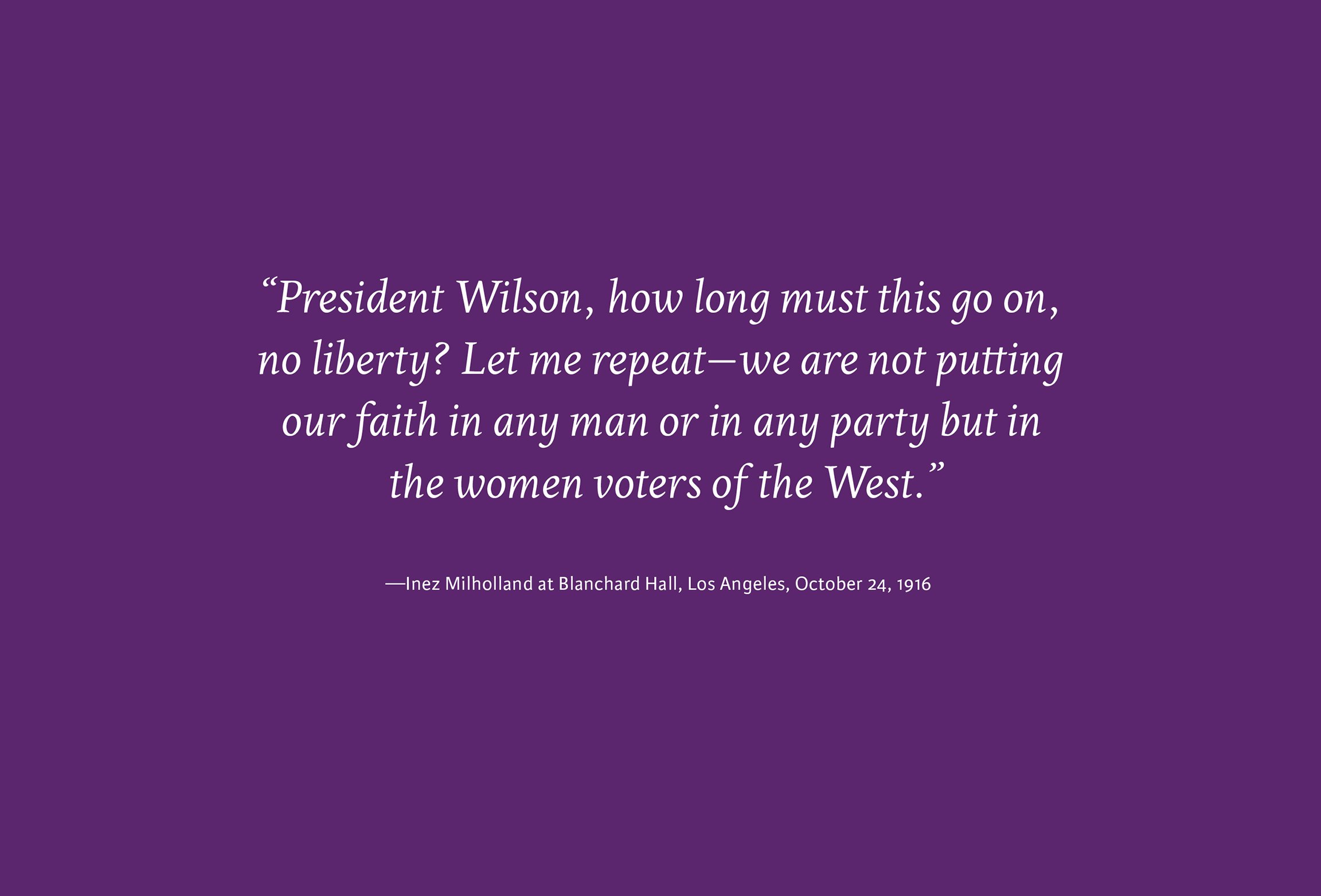

With the Presidential and Congressional elections just a few weeks away, their message for those women voters of the West was simple: stand together with suffragists in the Eastern states by casting a protest vote against President Wilson, the Democratic incumbent who had failed to make their cause a national priority for his administration.

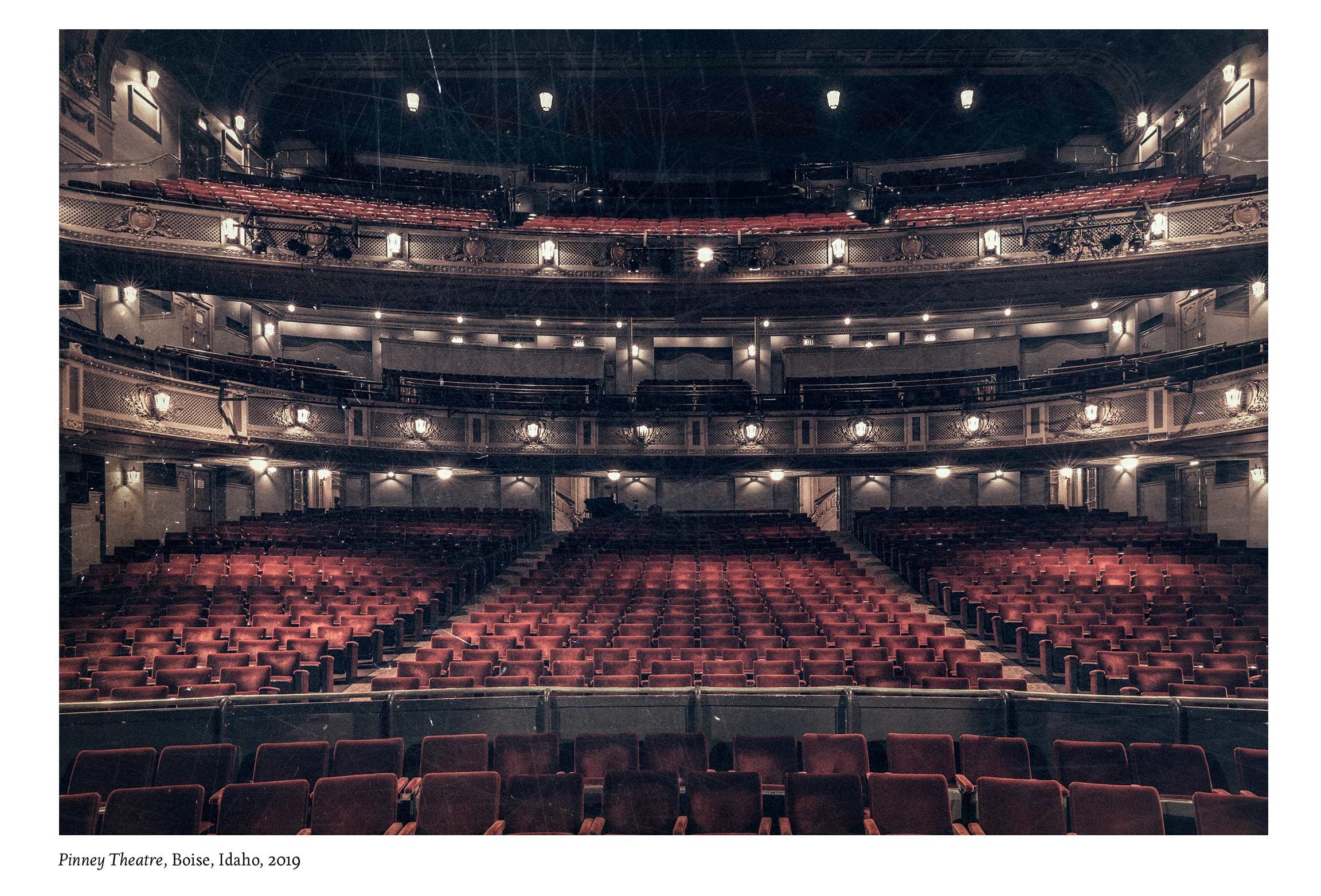

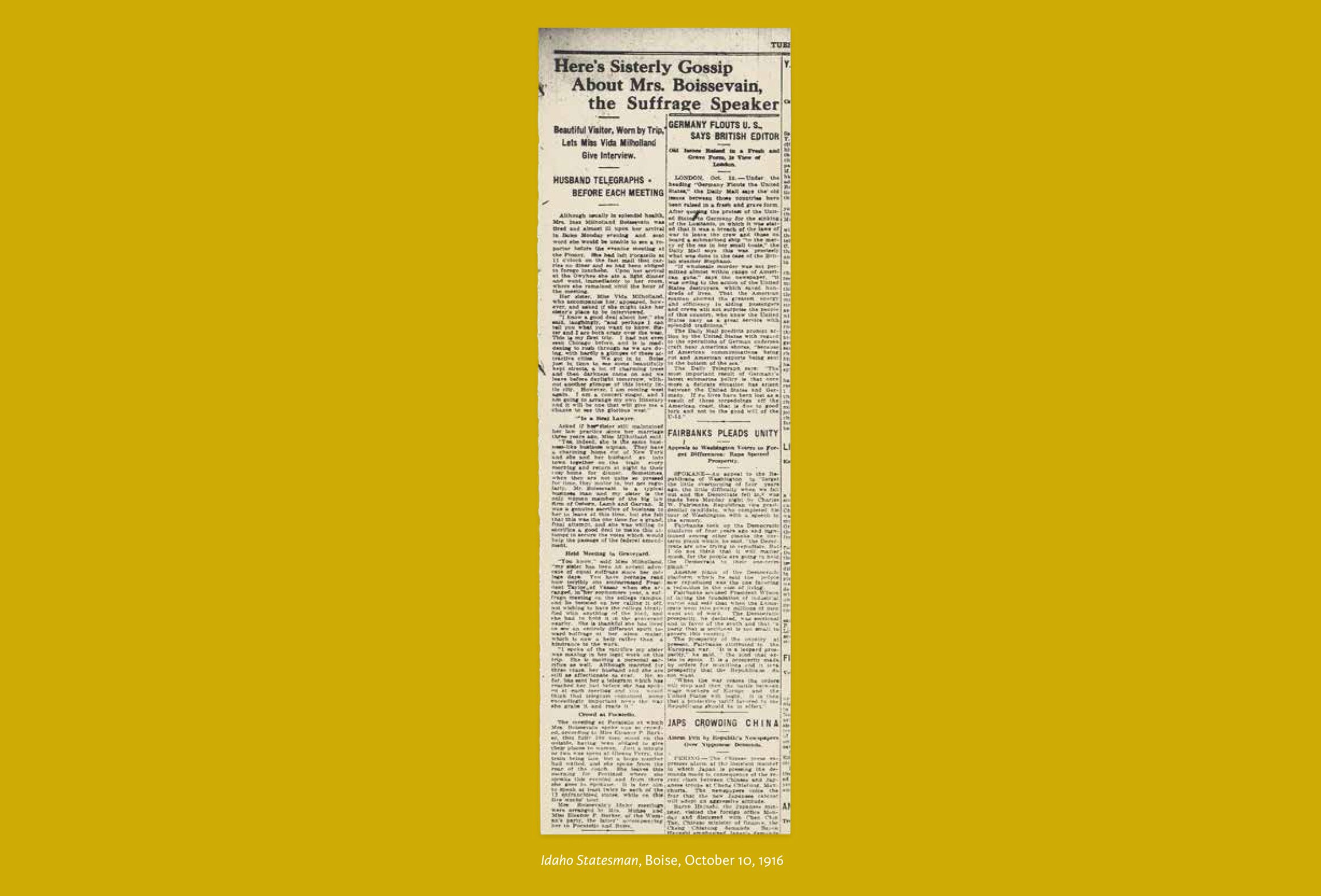

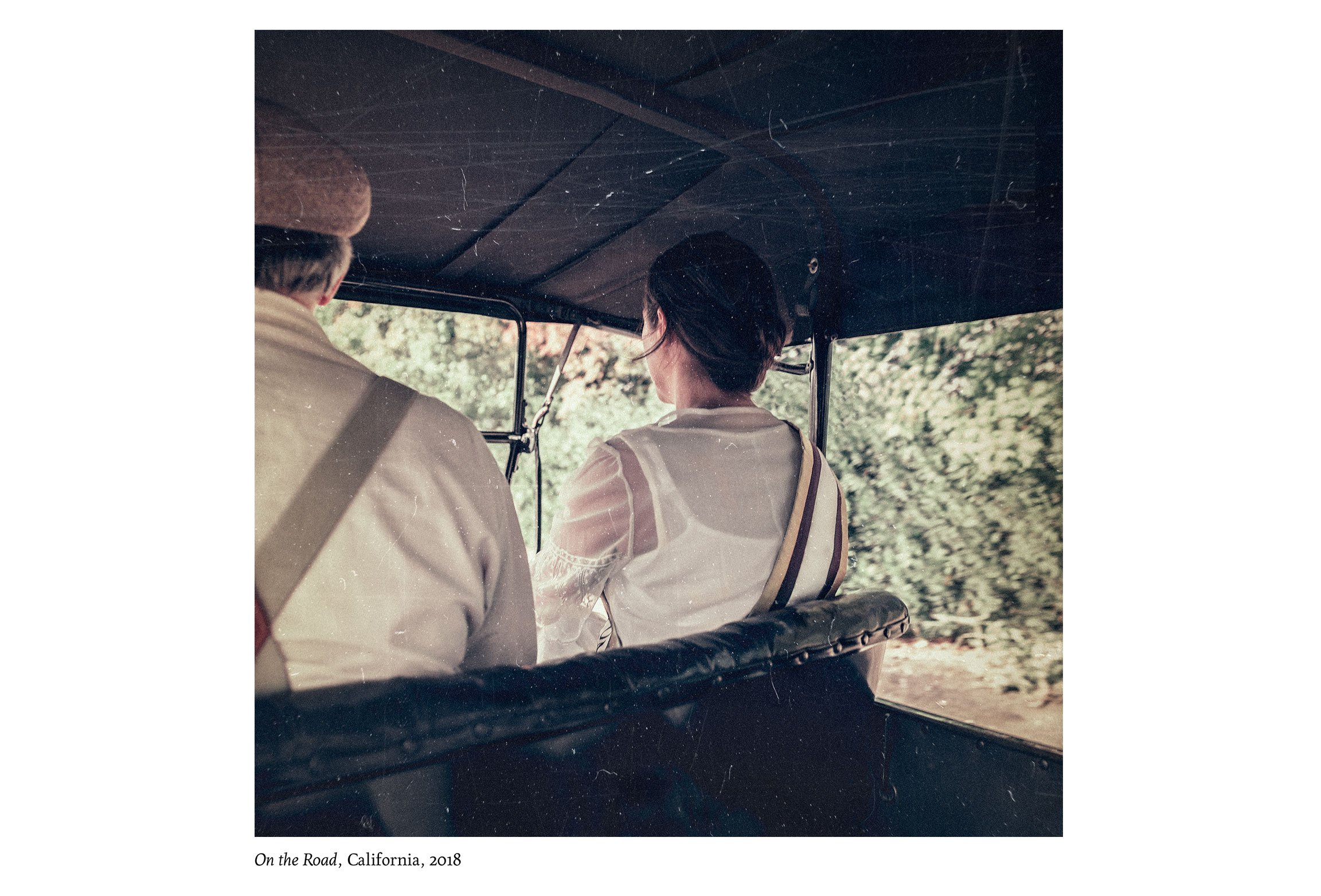

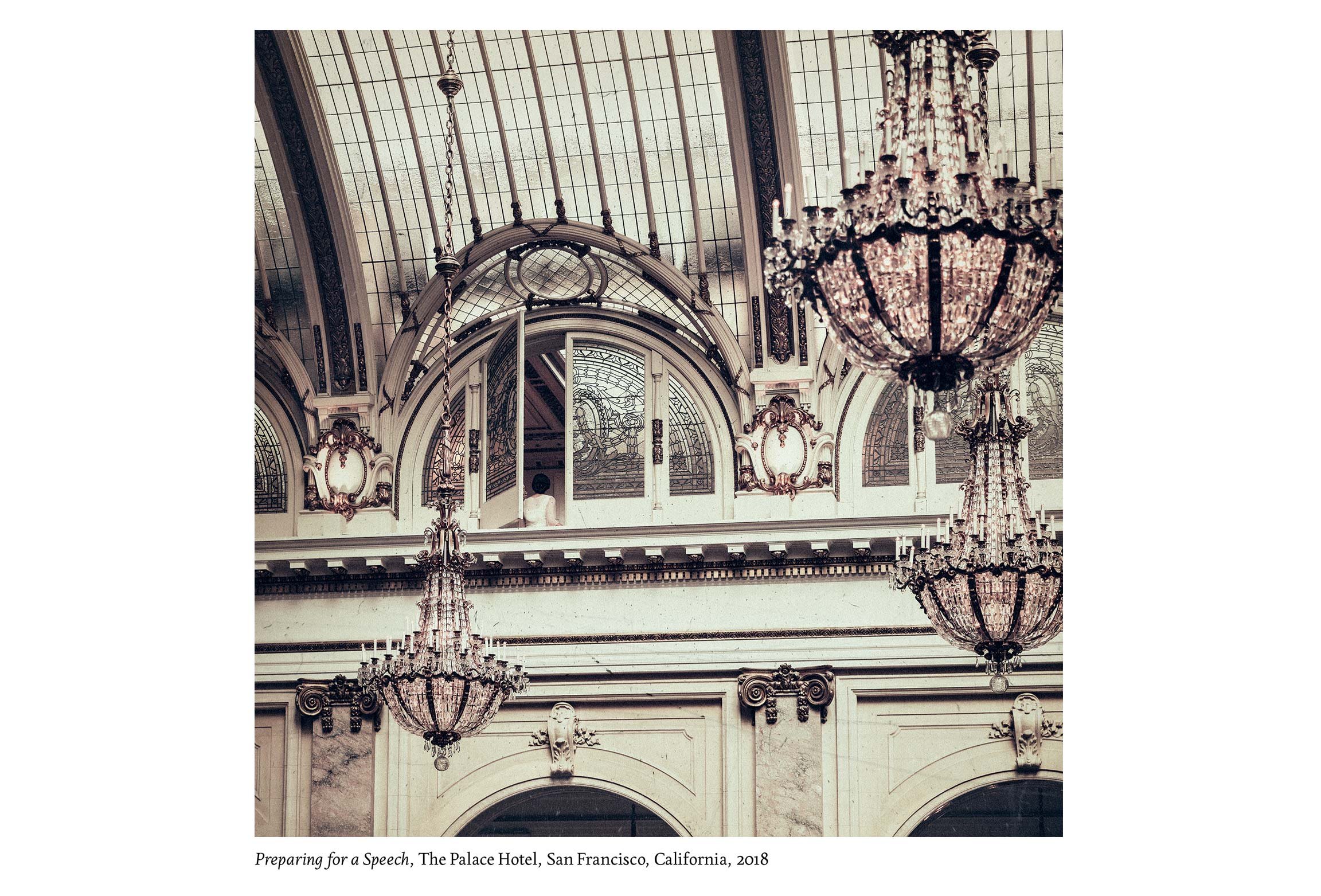

Traveling with her sister Vida, Inez embarked on a grueling campaign traversing eight states in 21 days. Her itinerary, brutal even by today’s travel standards, consisted of street meetings, luncheons, railroad station rallies, press interviews, teas, auto parades, dinner receptions, and speeches in the West’s grandest theaters.

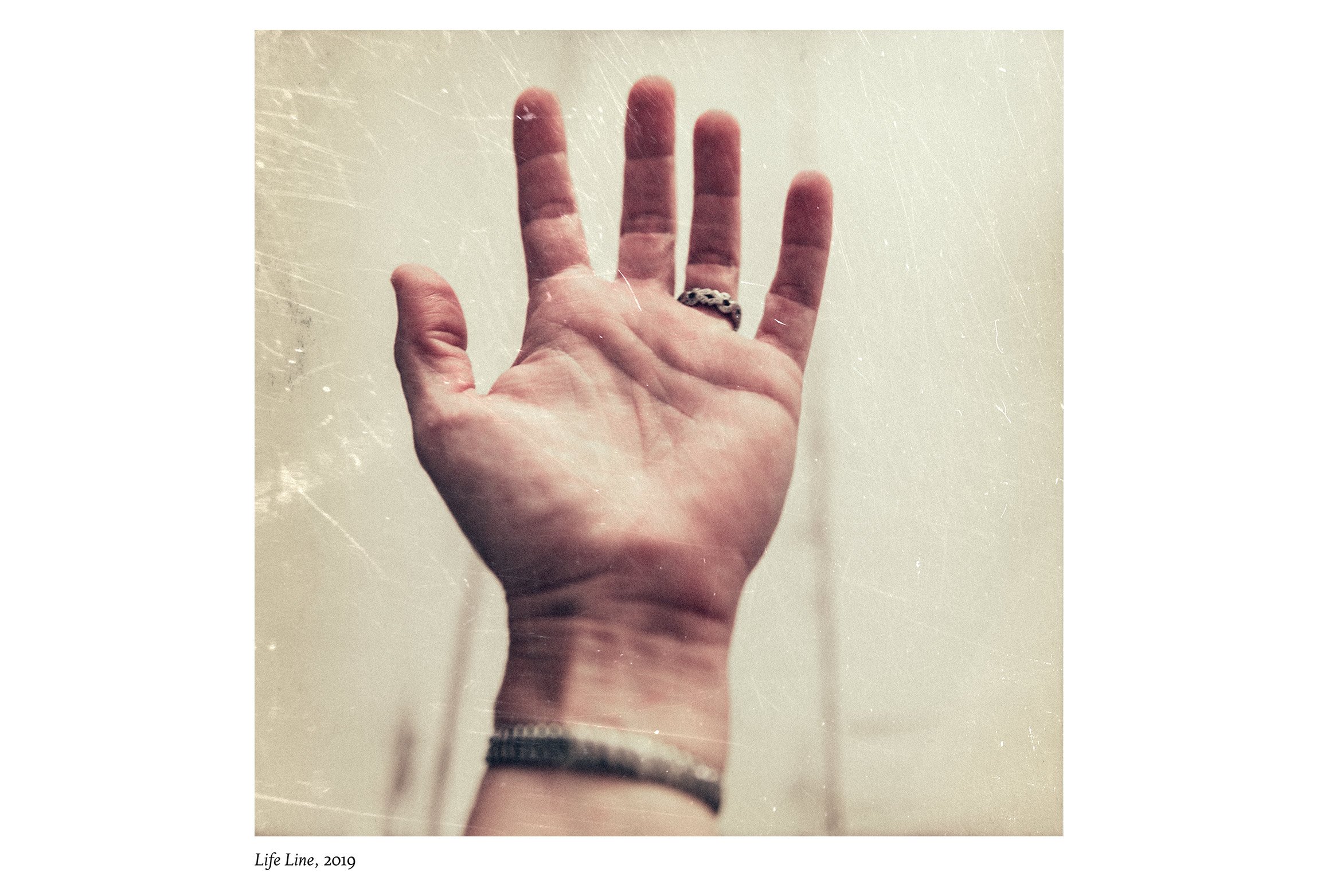

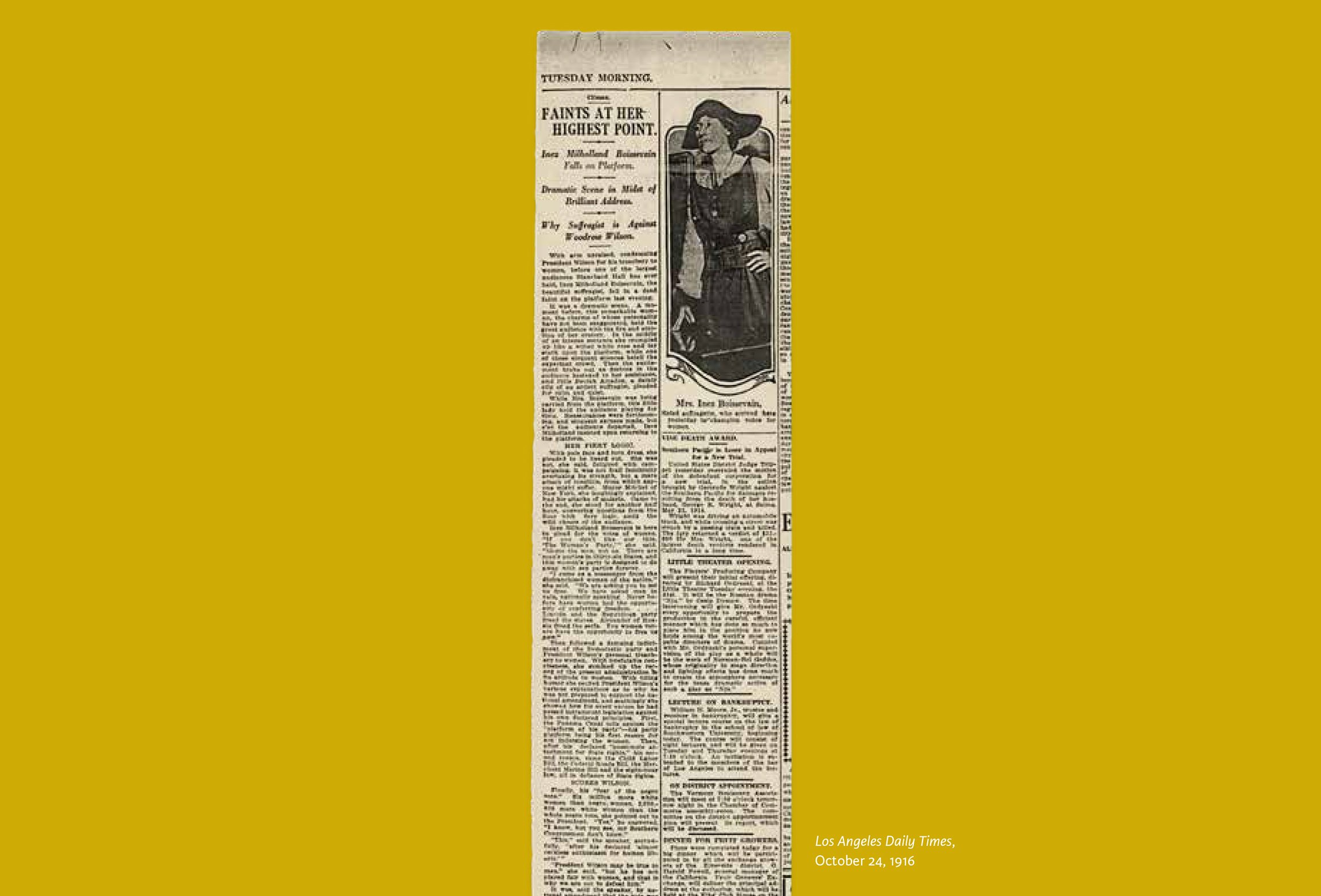

Arriving in Los Angeles on October 23, Inez delivered her last speech to about 1000 people at Blanchard Hall, where she collapsed on stage while speaking. She returned 15 minutes later to finish while sitting in a chair. Her final public words were, “President Wilson, how long must this go on, no liberty?”

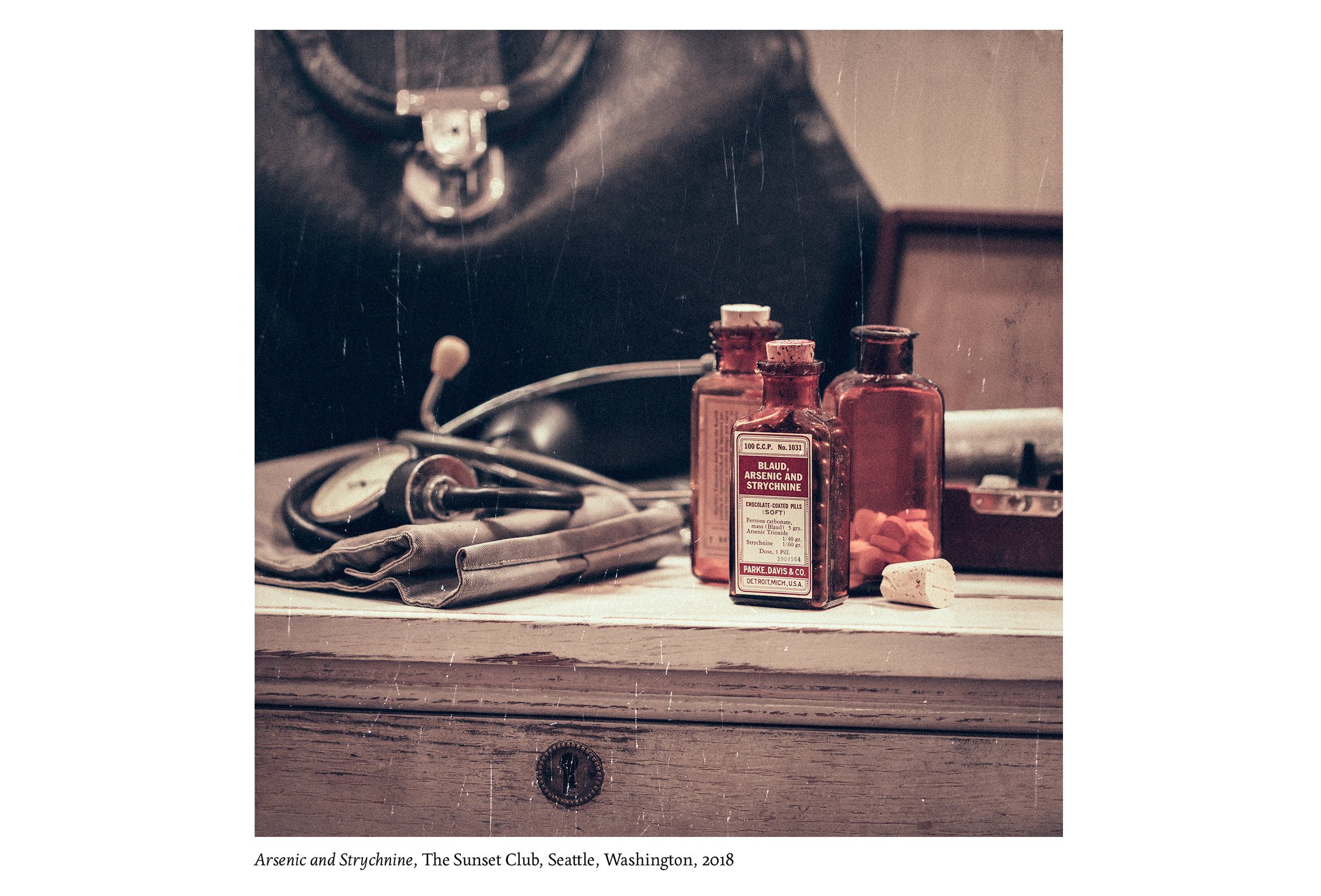

Although she tried to be “indefatigable” according to the Los Angeles Daily Times, Inez’s rapidly deteriorating health forced her to stop campaigning. She died only one month later on November 25, 1916 at the age of 30—a martyr of the American suffrage movement.

Background

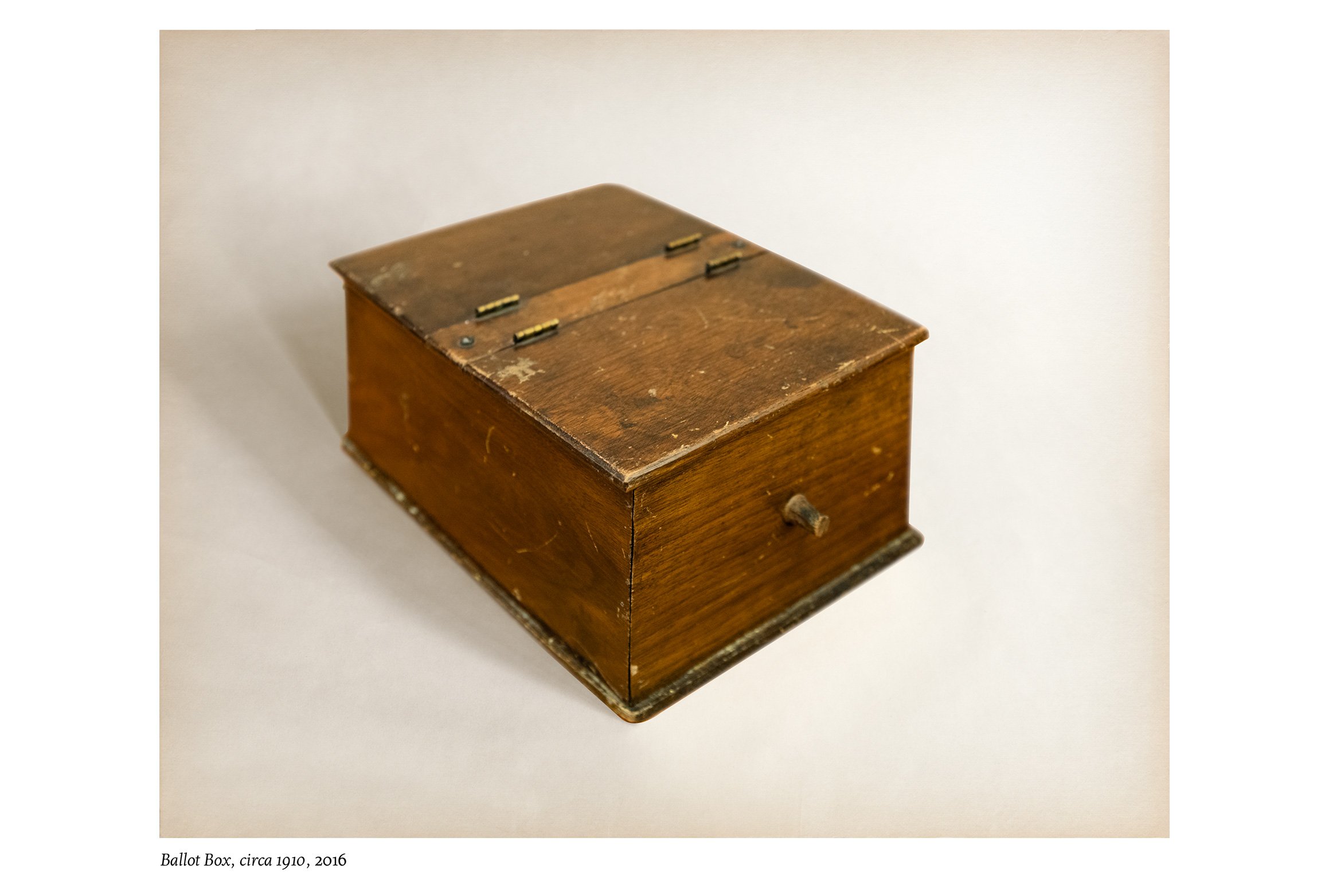

Over the course of 70 years, three generations of Americans sacrificed and suffered while working tirelessly to win the vote for American women. Women were never given the vote. They had to fight for it through the involvement of hundreds of thousands of Americans trying to win public support for their cause thereby creating the Women’s Suffrage Movement.

Inez Milholland’s campaign trail as Special Flying Envoy for the National Woman’s Party, 1916.

From well before the Civil War to 1920, American women were part of a monumental struggle for their own independence. During this long period, women were without a direct political voice and were unable to hold office, have a say in political matters, or even own property. Often they were viewed as either belonging to their fathers or their husbands. And married women had less rights than children.

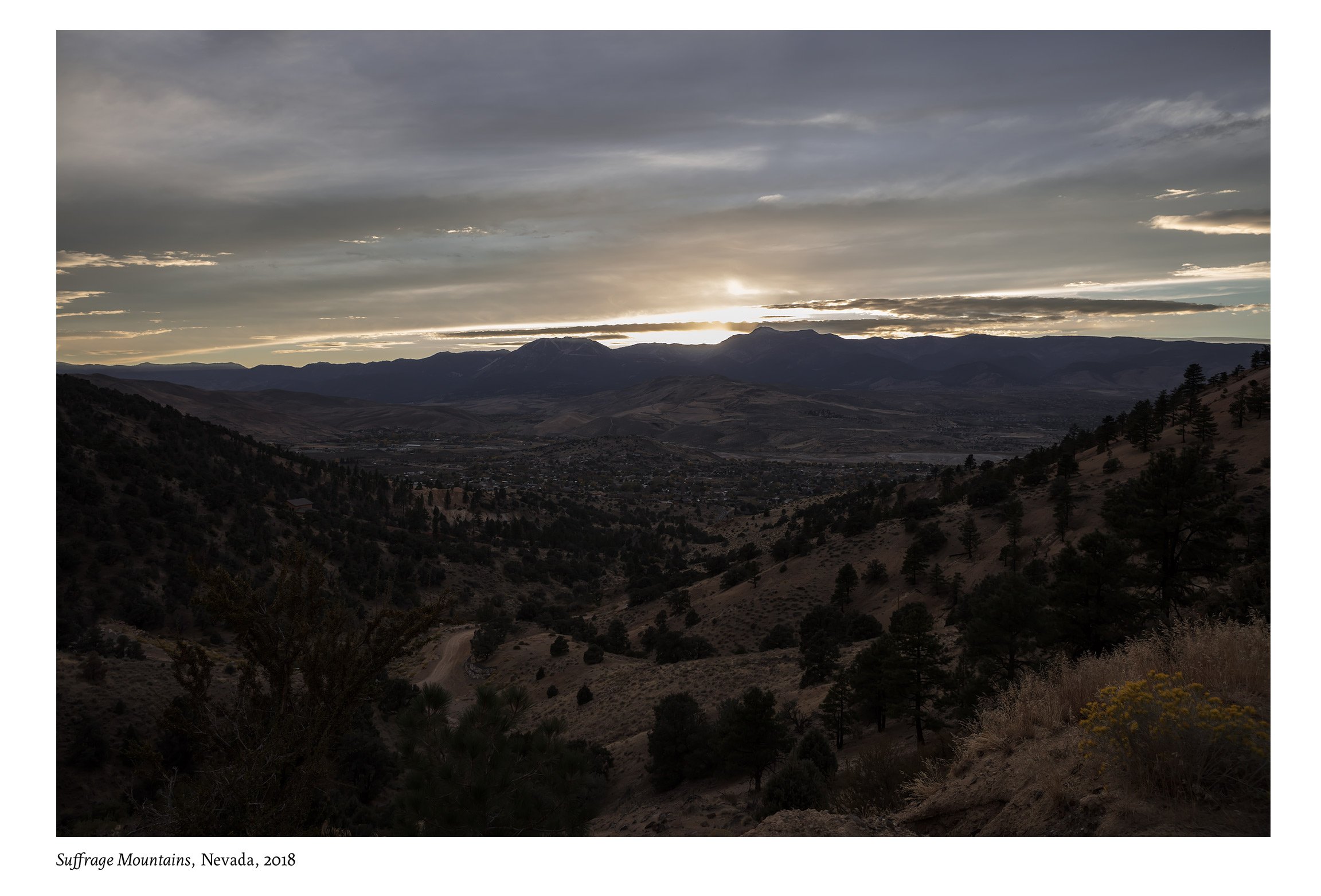

In response, supporters worked state by state challenging male voters to live up to their democratic ideals. And in some states they were successful. By 1916, 12 states—mostly in the west—had some form of suffrage for women. But when the suffragists took the same argument to a national level, they found little support.

1914 Map of Women’s Suffrage in the United States of America

The first two decades of the 20th century were a critical period in which suffragists overcame, or walked through every conceivable obstacle in their struggle to enfranchise half of the United States population.

Curiously, this time in American history is not well known. Why are we unaware of what women had to go through to obtain their dream of a government that is truly of the people, by the people and for the people?

Possibly, the length of time and complexity of the movement’s history could be seen as contributing factors. Powerful and long-standing opponents were barraged with an assortment of overlapping strategies and actions coming from both the state and national levels. There were 40 separate referendum campaigns in 26 states during the early 20th century alone. On the national level, different major women’s associations were competing for leadership and squabbling over emphasis and tactics: from prohibition to only focusing on a national amendment and forgoing a state-by-state route. Various strategies were used to turn the tide running the spectrum from traditional to progressive and even militant methods — furthering the confusion and divide that dominated the social movement.

Nevertheless these women and their male supporters were persistent and in August of 1920 the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed giving most women the right to vote. Although, sadly, it would take until the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to give most women of color the vote. And until 1962 when Utah was the last state to guarantee Native American voting rights.

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Inez began to work for suffrage while still a student at Vassar College when she formed a suffrage society made up of two-thirds of her classmates. Since discussion of suffrage was forbidden on campus by Vassar President Taylor, meetings were held in a nearby graveyard.

By profession, Ms. Milholland was a practicing lawyer in New York state. She attempted to enter Yale, Harvard and Columbia University law schools, but was denied admission because she was a woman. She obtained her law degree from New York University School of Law. At the beginning of WWI Milholland became a war correspondent, but was denied access to the front lines due to her gender. She contined to write anti-war articles which led to her censure by the Italian government and her expulsion from the country.

In 1915, she was a part of the Henry Ford Peace Ship Expedition that unsuccessfully attempted to broker an end to WWI.

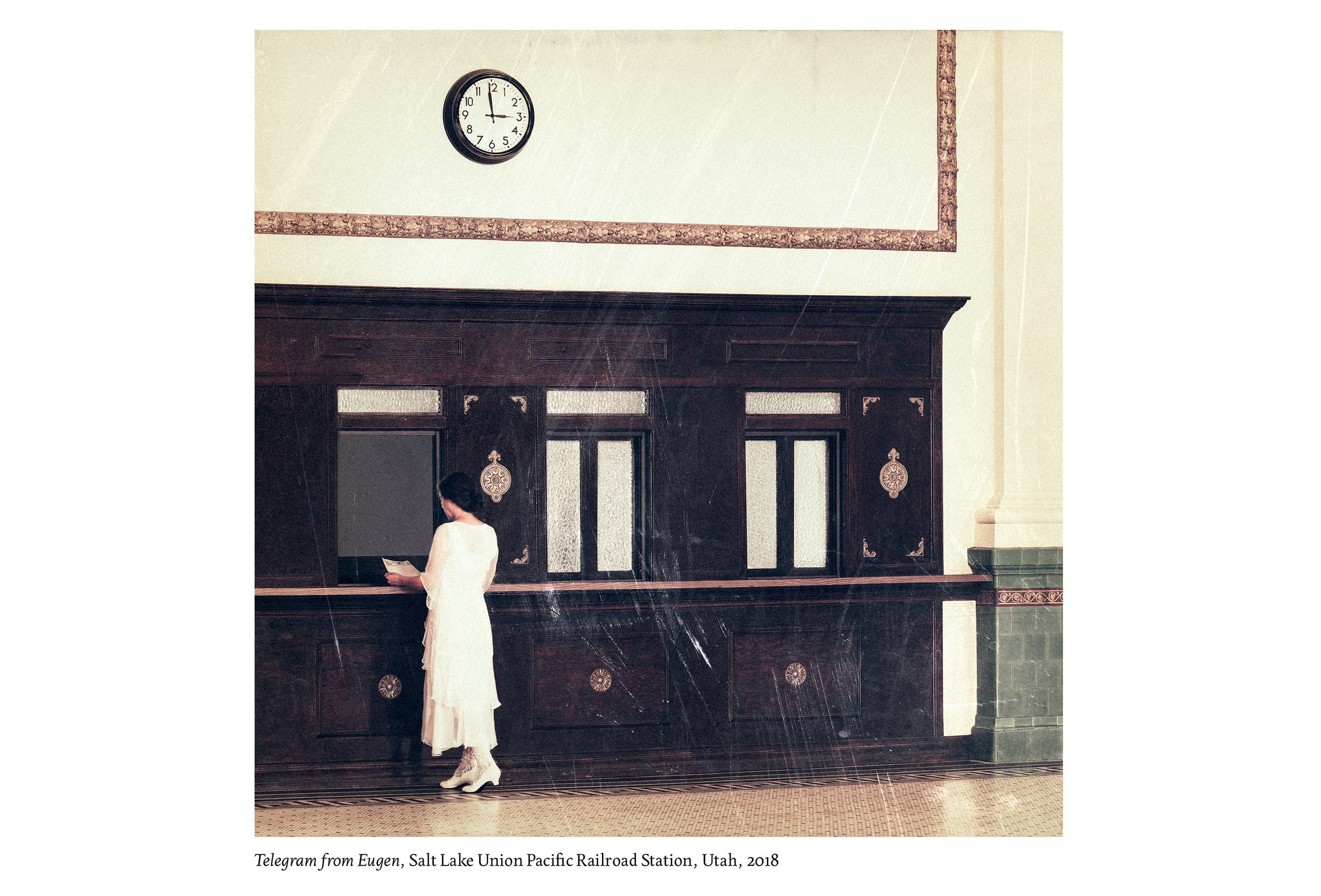

Her marriage to foreigner—Eugen Jan Boissevain—in 1913, caused her to lose her American citizenship and forced her to become a citizen of Holland. Even though, she was born and worked in America, she had no protection under the United States government. Of note, men did not loose their American citizenship by marrying a foreign woman.